Underwater World

Turkey is surrounded on three sides by the sea, and from the earliest times important trade routes have skirted its shores, with many of its coastal cities serving as ports of call.

The Phoenicians penetrated to every corner of the Mediterranean, while in Roman times ships laden with Egyptian wheat and Anatolian wine followed the coasts of Asia Minor on their way to Rome. This was the time when Asia Minor was being plundered of its artistic treasures, and some of the ships carrying these sank off these shores together with their priceless cargo.

Turkish waters conceal wrecks dating from every period from ancient Syrian times up to the 19th century, but most of those that lie at a depth of less than 40 metres have already been looted and form the source of the amphorae that decorate various hotels and restaurants, while those that lie a little deeper are in immediate danger. It is for that reason that we have not divulged the exact position of the wrecks that still await investigation.

Introduction to the Underwater World

The darp depths of the sea and the secrets it conceals have always exerted both fear and fascination, but even now, when man is exploring outer space, underwater exploration is limited to a depth of a few hundred metres below the surface.

The first diver was Gilgamesh, the hero of the Sumerian epic of 5,000 years ago, who dived to the depths of the sea with heavy stones tied to his legs to obtain the plant of everlasting life, while in early Greek mythology Theseus proved to Minos of Crete that he was the son of Poseidon by throwing a ring into the sea and diving down to recover it returning not only with the ring but also with a golden crown given him by the goddess Amphitrite.

The first actual diver known by name is Skyllias, who, according to Herodotus, was employed by the Persians to recover objects of value from sunken ships. Thucydides mentions the use of divers in the siege of Syracuse, while in the siege of Tyre by Alexander the Great in 332 B.C. divers wearing goat-skin suits were employed to destroy underwater barricades.

Aristotle mentions a type of apparatus that would allow divers to remain underwater for some time, while Pliny talks of divers using air tubes. In 385 A.D. Vegetius describes a diving-helmet with breathing tubes, while Leonardo da Vinci has left sketches of both submarines and diving gear.

Throughout all this time, however, sponge divers continued to use only to most primitive equipment, consisting of a heavy stone attached to the legs or arms by means of which the diver could descend to the seabed. Having gathered his sponges he would release the stone, which would then be drawn up again to the surface by a rope attached to it.

The sponge divers were very skilful indeed, and this accounts for the outstanding excellence of the divers employed in the Ottoman fleet from as early as the time of Mehmet the Conqueror right up to Sultan Abdulaziz.

Diving Technique

The most important problem facing the primitive divers was the length of time they could stay under water. This they attempted to solve by rubbing their bodies with oil, which probably protected them against the cold and so reduced the consumption of oxygen, and by holding a sponge in their mouths, which probably had a psychological effect on the respiration.

The invention of air compression in the 18th century made developments in diving techniques possible, and in 1827 Siebe invented the diving suit with helmet. In this, however, the lead weights attached to the feet severely restricted freedom of movement.

In 1943 diving was made much easier by the invention of the Aqualung by Gagnen and Cousteau. This automatically adjusts the pressure of air supplied according to depth and water pressure. Using an aqualung a diver can move freely under water without any connection with the surface.

The diver setting out on underwater archaeology must have a rubber suit to protect him from the cold, a waterproof watch, a mask to allow him to see under water, a knife to extricate himself from weeds etc., fins to facilitate movement, a weighted belt, an under water camera, measuring instruments, plastic paper and a special underwater pen.

Underwater Archaeology

Underwater archaeology consists of the exploration and investigation of submerged cities or the wrecks of sunken ships.

The first recorded attempt at underwater archaeology was made in Lake Nemi near Rome in 1446. Divers were brought from Genoa to investigate rumours of sunken ships, and after combing the lake they returned with the fragment of a large statue. In 1555 a diver went down in a diving suit and carried out a further survey, bit it was not until the time of Mussolini that the ships and their contents were finally recovered by the rather drastic means of draining the lake.

In 1900 a diver gathering sponges off the little island of Andikithria in Southern Greece found a bronze arm. Further excavations resulted in the recovery of 36 statues, 31 fragments, and a marble horse, as well as numerous implements and utensils. In order to recover these, however, it was necessary to dive to a depth of over 54 metres. This made it impossible for a diver to make more than two dives of five minutes each per day, and even then three suffered from ‘stroke’ and one died.

Another chance discovery made by sponge divers in 1907 revealed the existence of a wreck off Tunis which yielded enough finds to fill 6 rooms of the Bardo Museum.

Rhodes amphora. Beginning of 2nd century A.D.

As a result of the great advances made in diving technique after the Second World War a number of wrecks were found off the French and Italian coasts, but the first underwater plans were those made in the investigation of the submerged sections of ancient cities. Work of this kind was first carried out in the ancient city of Tyre, and revealed both the size of the old port and the ship-building techniques employed at that time. Work on other submerged cities in Israel, the Lebanon and Crete showed that ancient writers had often given wrong information, but it is the Russians who have given the greatest importance to this type of archaeology and who have succeed in excavating and drawing up plans of a number of ancient cities lying submerged in seas and lakes.

A great step forward in underwater archaeology was made in the excavation of the wreck of the Grand Conglobe off Marseille, which was carried out by the Director of the Marseille Museum and Cousteau. Here photographs were taken of the finds in their original position before removal, and work on the detailed plan of the wreck continued for several years.

As the time a diver can remain under water is severely limited new methods of drawing up plans had to be invented. One of these, which was employed on the wreck of the Spargi off Sardinia, consisted in lowering a grid square over the wreck. These squares were divided into yet smaller squares, thus enabling the necessary measurements to be taken quite easily. This was the method later employed at Bodrum and Yassiada in Turkey.

As for the actual salvage of sunken ships, the wreck of a ship that had sunk off Stockholm and whose existence had been known since at least 1628 was finally brought to the surface in 1956 in a perfect state of preservation, while another wreck, this time off Kyrenia in Cyprus, was recovered in 1967 and is now exhibited in a special temperature-controlled room in Kyrenia Castle.

Underwater Archaeology in Turkey

In deep water sponge-fishers use a type of drag-net consisting of two wheels with a heavy chain between them that scrapes over the sea-bed and fills the net behind with sponges and other sea-growths. Very often amphorae are brought up in these nets and are usually broken up and thrown back into the sea. On one occasion, however, in August 1953, the fishers were amazed to find the bronze statue of a woman brought up in this way. This, too, would have been thrown back had it not been for Erhan Erbil, a fisher from Bodrum, who insisted on taking it to land.

Here it was examined by Prof. George Bean, who identified it as the goddess Demeter and dated it to the 4th century B.C. It was later taken to the Izmir Museum.

Interest in underwater archaeology was sparked off by this discovery, but it was not until 1958, when Peter Throckmorton, a New York reporter who came to Turkey to do a series of articles on the Bodrum sponge fishers, that further developments took place. Throckmorton’s attention was immediately attracted by the ancient amphorae to be found in almost every home, and he decided to switch the subject of his inquiry to the question of sunken ships off the Turkish coast.

With the help of a local captain and a photographer from the Frogmen Club at Izmir they finally identified a number of ships that had been wrecked on the treacherous sandbanks at Yassiada near Bodrum. These included two wrecks, one Roman and the other Byzantine that had been protected from the depredation’s of sea fauna and flora by a blanket of sand, and a few years later archaeological investigations were finally carried out on these ships.

The Gelidonya Wreck

Peter Throckmorton stayed for two years with the Bodrum sponge fishers in the hope of discovering the ship laden with bronze that had been observed by Captain Aras off Gelidonya Point near Antalya.

Exploration was begun in 1959 and was rewarded by the discovery of a heap of bronze ingots in the form of ox-hides, on the strength of which the wreck that contained them could immediately be dated to the Bronze Age.

Throckmorton drew the attention of the University of Pennsylvania Museum to the find, and in 1960 George F. Bass, an expert on the Mycenean Age, was given permission to carry out excavations on the wreck. Thus began the first official underwater excavation in Turkey.

Fragment of a straw mat, after 3300 years underwater

A diving crew was set up and trained with the help of Frederic Dumas, one of the experts from the Cousteau team, and the expedition set out for Gelidonya Point in a sponge-fisher’s boat. The wreck, however, had become so clamped to the rocks that it was impossible to move it, and sections could only be removed by hacking them off with a chisel.

In any case very little of the wooden hull had survived, but fragments of the shell were found nailed to the hull in exactly the same way as described in the Odyssey. In addition to the ingots there were large quantities of bronze hammers, spades, needles, knives and other implements, which indicates that this was a merchant ship, while the fact that the bronze comes from Cyprus would suggest that the ship was on its way from this country. The existence of moulds, together with copper ore and tin, shows that the bronze was being made on board during the voyage.

The finds discovered indicate a date in the 13th century B.C., which means that this is the earliest boat so far excavated. The objects found in it formed the basis of the Museum of Underwater Archaeology in Bodrum.

The Byzantine Wreck

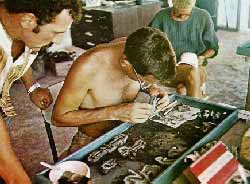

This wreck was discovered about 150 metres from the island of Yassiada at a depth of 30-36 metres. The excavations were carried out by a team consisting of an architect, an artist, a photographer and a number of archaeologists under the direction of George F. Bass. Most of them learned to dive only after arriving in Bodrum as the aim was to make divers of archaeologists rather than archaeologists of divers.

A flat-bottomed boat was placed over the wreck to serve as a diving-platform and anchored on three sides to prevent it from drifting with the winds and currents. Dives were made twice a day, the morning dive lasting 25-30 minutes, the evening dive rather less.

The wreck was cleaned with wire brushes to remove sea-weed and make photography possible. The Dumas grid system was placed over the spot where the cabin must have been and measurements made from there. Plastic labels were attached to the finds and sketches were made on special plastic paper with underwater pens. Finds were brought up to the surface only after photographs and sketches had been made.

Of the 900 amphorae on board 100 were brought to the surface. Some were raised by being turned upside down and filled with air and allowed to float up to the surface, others were attached to balloons. Deposits were immediately removed as otherwise they hardened and cleaning became absolutely impossible. They were also kept in fresh water for a time to prevent cracking.

Towards the end of the 1961 season a steelyard was discovered bearing the name of the captain -Georgia Presbyterou Nauklero. On one end of the bar was a leopard and on the other a pig’s head, while the handle consisted of a statue of Athena, showing that the old gods and goddesses retained their influence well into the Byzantine era. The gold coins found in the wreck indicate the reign of the Byzantine Emperor Heraclius, the latest of the coins being dated 625.

The excavations were finally completed in 1964. The work had lasted for four seasons and over 3,000 dives had been made. The latest techniques were employed in these excavations and the treatment of the finds served as a model to other underwater excavations. This excavation is also of importance in being the first excavation to have been carried out on a Byzantine wreck.

Bust of Athena used as steelyard handle.

Byzantine oil lamps

Byzantine jars. The jar in sed for

decanting wine from amphora

Gold Coins of the Emperor Heraclius

Oxidised iron implements are taken out from

the moulds by splitting into two.

The Roman Wreck

In 1967 the University of Pennsylvania Museum excavation team under George F. Bass began work on a Roman wreck lying about 10-15 metres from the Byzantine wreck described above, at a depth of 36-42 metres. Like the Byzantine wreck this was also a merchant ship with a cargo of amphorae. The excavations were carried out in the years 1967-69, with a few days additional work in 1974. The latest underwater methods were employed in this excavation, which constituted the deepest underwater investigation yet to be carried out. Underwater stereo photography was used to draw up the plans, the resulting photographs being projected three dimensional in red and blue lights on a secreen, with an expert wearing special glasses tracing the lines on paper with a special instrument.

One of the great difficulties in underwater archaeology is the removal of sand from the area of the wreck. Here water-pumps were used, with fire hoses aimed directly at the sand heaps.

Another difficulty is the fact that underwater investigators are unable to communicate either with one another or with those at the surface. In this excavation an underwater telephone booth was constructed consisting of a plexiglass hemisphere into which air was continually pumped. The divers could go into this booth and remove their masks and air-tubes and talk to one another. At the same time they could communicate with the archaeologists at the surface by means of the telephone. This also provided a place of refuge which the diver could reach quite easily in an emergency instead of swimming some 40 metres to the surface.

Another interesting feature was the decompression chamber hung on chains and held at any desired level. The chamber had a continual supply of fresh air, and was furnished with chairs and lamps so that the divers could sit comfortably reading or making notes while carrying out decompression.

Television was employed to follow the work of the underwater investigators, so that the archaeologists on the surface were able to follow and direct operations at every stage. At the same time students could observe the work closely, which made their own task much easier when they ventured underwater themselves.

As the boat was lying on sand the wooden sections were in quite a good state of preservation, and enough was left of the stern to give a good idea of its original shape.

The ship had been carrying 1100 amphorae, but as their provenance is not known we are unable to say from what port the ship was sailing. A number of copper coins were found, but these were so eroded that they were of no help in dating. The finds in general, however, point to the 4th century A.D., and this date is corroborated by four oil-lamps bearing the stamp of a workshop in Athens.

There were only a few earthenware plates, so it would seem that only wooden plates were used by the crew. The fact that no human bones were found indicates that the sailors were able to make their way to the island of Yassiada, while the fact that this island has a large rat population though the neighbouring islands have none seems to suggest that the rats also succeeded in reaching dry land.

Raising ship’s timbers by means of a balloon

A yellowish glass vase from the Roman wreck

The 17th Century Wreck

In the course of excavating the Roman wreck another sunken ship was found completely buried under the sand. A small pitcher, and earthenware pot and some green glazed jars belonging to this ship were found in the Roman wreck, and a silver coin of Philip of Spain was found nearby.

The wreck was re-covered with sand to protect it from sea fauna and flora and now awaits the interest of future investigators.

Wrecks off the Turkish Coast

The ancient trade routes followed the Turkish coast, with the result that many ships lie sunk off these shores. Most of these were merchant ships laden with amphorae, and it is these heaps of amphorae, and it is these heaps of amphorae that now indicate the presence of a wreck.

The first investigations off the Turkish coast were carried out in 1958-59 by Peter Throckmorton and some sponge-divers, but these divers can rarely dive deep than 60 metres, and even then only for a few minutes at a time.

The statue of Demeter was discovered in 1953, and in 1963 the statue of a negro boy, both of them being brought up in a drag-net. These statues lay at a depth of 85 metres and could not have been brought up by ordinary means. The discovery of a statue of lsis at the same spot as the negro boy indicates the presence of the wreck of a ship that had been carrying art treasures, and it was upon this discovery that the University of Pennsylvania Museum decided to undertake investigations.

In the 1965 excavations a proton magnetometer, a closed circuit television and a towvane were employed. The proton magnetometer, which is a sort of underwater detector, proved to be of no very great help, but the television, although it had the disadvantage of being two-dimensional, was of assistance in discovering some wrecks. The Towvane is a one-man underwater capsule that affords a 360 view around one, but this proved very difficult to use.

In the 1967 investigations sonar and a two-man submarine were employed. The sonar made it possible to examine the seabed to a depth of 360 metres and to detect the presence of any mounds. Whether these mounds were geological nesulted from the presence a wreck could be partly detected by the profile of the tracing. In the area in which the negro boy was found only one spot indicated the presence of a wreck. The two-man submarine was sent down and the wreck of a Roman ship laden with amphorae was discovered at a depth of 84 metres.

In 1971 a search was begun for a boat with a cargo of copper that was supposed to have sunk off Antalya. Some pieces of copper had been recovered and with the help of these the boat was dated to the 15th century B.C. The sonar indicated the possible presence of a wreck at a depth of 30 metres near the mouth of the Manavgat River, and if this has not already been plundered it awaits scientific investigation. No excavations were carried out as investigations at this level can be carried out quite easily without special equipment.

In 1971 a wreck dating from the 4th or 5th centuries A.D. was discovered at a depth of 45 metres near Fugla Point, while a number of other wrecks were found in the Antalya region.

Other wrecks were found off Marmaris, but these had already been plundered, while another, with a cargo of amphorae was in a position that made excavations extremely difficult.

In general wrecks lying at a depth of less than 15 metres have been totally destroyed by the waves, while those at a depth of less than 40 metres have been plundered. Thus it is only wrecks lying at depths greater than these that are of real interest.

A great many fascinating sites, await the attention of underwater archaeologists in both seas and lakes in this country, and there is plenty of evidence to show that Turkey will prove to be the richest country in the world in underwater archaeology.

Underwater Finds in Turkish Museums (in 1975)

Finds from the scientific excavations carried out under the direction of George F. Bass are exhibited in the Bodrum Museum, but many objects that help to give some idea of the extent of underwater archaeology in Turkey are to be found in various other museums. It would be out of the question, of course, to present a complete list of all the underwater finds exhibited, and we shall rest content with a representative selection from the Turkish museums.

Bodrum Museum

Bodrum Museum contains the largest collection of underwater finds in the world and includes hundreds of underwater finds, in addition to those from the Gelidonya, Byzantine and Roman wrecks.

The finds exhibited here are of immense variety, and range from nautical gear and anchors of the type still used today to earthenware floats. Bodrum owes the wealth of its museum to its sponge-divers, and up to quite recent years a great number of finds were brought back to Bodrum Museum by the 300 boats that set out every year to gather sponges. Objects recovered from the sea can also be seen exhibited here and there outside museum itself, while amphorae of a beauty to excite any art lover lie concealed in corners of the houses awaiting the attention of the scholar.

Bodrum Museum was first opened as a depot to house the finds brought to Bodrum from the Gelidonya wreck in 1960, but very quickly grew into one of Turkey’s largest museums.

The Goddess Isis

The sailors who set out to sea in their small boats to face unknown dangers sought the protection of gods and goddesses

who could keep them from harm. The old Greek and Roman sailors found what they were looking for in a goddess of Egyptian descent. This was the goddess lsis, the cow-horned goddess. Her promises of an everlasting life after death won her the allegiance of poor people who had little to hope for in this world, and figurines of the goddess were in great demand. One of these is the bronze statuette of lsis sold to the Bodrum Museum by Riza Sarac. This was found in the sea off Yalikavak near Bodrum in 1963.

This is a bronze statuette representing a standing women. The goddess is looking to the right and has on her head the horns of a cow and disc crown The hair is parted in the middle and gathered into a bun at the back of the neck under the crown. There are four plaits of hair at the front and back and long-ear-rings in the ears. She is wearing a triangular, sleeveless chiton with collar, which reveals the right breast and is covered by a mantle. The mantle leaves the right shoulder completely bare and hangs down over the left shoulder, producing a series of folds under the left arm. The light dress under this mantle reaches as far as the ankles. The right arm is broken off at the shoulder and is missing, while the left arm is slightly bent at the elbow and attached to the body. The left hand is broken off at the wrist and is missing. The way in which the dress sweeps out at the back suggests that the right foot was placed to the rear. This statuette probably dates from the Hellenistic period.

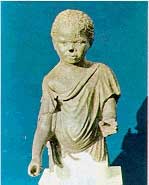

Statue of a Negro Boy

This is a bronze statue broken off below the waist. The figure is of short stature, with curly hair, a flat nose and thick lips. The hair, eyebrows, mouth, nose and lips are all typically negroid in character. There is a hole in the pupil of the left eye, but the hollow in the pupil of the right suggests that the pupils were made of precious stones. The ears are small. The upper portion of the head and the nostrils are broken and missing. An examination of the head shows that the bronze was cast in sections and then assembled.

The boy is wearing a tunic which completely covers the right shoulder and is brought over to the left. It was probably held on the right shoulder by a buckle. A large fold can be seen in the collar. The material covers the upper part of the arms and produces very broad folds under the armpits. The dress is very broad folds under the armpits. The dress is very full and is tied by a sash under the belly, which shows the swelling typical of malaria. The folds at the rear are triangular in form, but the back of the figure is broken and missing. The head is looking towards the front. The right arm is stretched slightly forward and the hand was probably holding a stick. The left arm is bent at the elbow. The hand is slightly open and seems to be grasping something.

This standing figure represents a malarial negro boy. He is probably looking after the geese. A large number of such statues on social themes were made in Hellenistic times, and this figure displays very typical Hellenistic characteristics. The lsis and Negro statues were both recovered from the same wreck.

This is a pot made of red clay with out-turned rim, projecting handles with half rings underneath, a round body and a wide base. The rim is broken and parts are missing. This probably belongs to the classical period (5th – 6th centuries B.C.)

Chamber Pot

This is a pot of brick-coloured clay with projecting rim, a cylindrical concave body and a handle in the form of a band. There is a deep crack in the bottom. A rare and interesting scene in Greek vase paintings is that showing a child on a chamber pot. This one, recovered from the depth of the Aegean, may well have belonged to the captain’s child.

Lead Brazier

This is a brazier made of lead, with a semicircular fireplace, and a rectangular section in front of this. Behind the fireplace there is a reservoir in the form of a pipe for boiling water. This reservoir also goes under the fireplace, thus serving a double purpose in providing a supply of hot water and at the same time preventing the lead in the fireplace from melting. This brazier may be dated to the 1st or end of the 2nd century B.C.

Float

This float is made of light brown clay and has a spherical body with a ring-shaped handle. It had sunk as the result of a perforation in the body and must have lain for centuries at the bottom of the sea.

Floats of oak bark are known to have been used in antiquity, but this is the first time an earthenware flat has been encountered.

Amphora With Handles

This is an amphora of light brown clay with a raised rim, no neck, two handles rising straight up from the shoulders and a lower portion in the form of a cone.

This is a very rare type of amphora. Owing to its weight and large capacity it must have been carried by two people by means of a pole passed through the handles.

This amphora closely resembles a grave find in the Silifke Museum, and probably belongs to the 4th or 3rd century B.C.

This is made of rough grey stone and is in the form of a square with curved top. In the centre there is a cross and on the cross the letters N and O. These are probably the initials of a proper name. The anchor has three holes. The one on top is for a rope, the two below for wooden stakes. This anchor probably belongs to the early Christian or Byzantine period.

In the centre is a square shank socket with tapering arms projecting out at each side. As the surface of the anchor head is heavily oxidised no names or religious signs can be deciphered. The anchor head found in the wreck of the Mehdiyye at Tunis weighs 695 kgs.

Lead anchors began to be used in ships from the 6th century B.C. onwards. This type of anchor consisted of a combination of wood, lead and iron. The body and arms of the anchor were usually of wood, while the connecting piece and anchor head were of lead. In some cases the clamps were of iron, and iron was used in the flukes. They lead anchor with preserved wooden section recovered from lake Nemi in Italy makes the reconstruction of this type of anchor possible (fig. 10). From the 2nd century A.D. lead anchors began to be replaced by iron ones.

This is a pot in the shape of a human head, with a single handle and a long round sharp rim at the very top. The hair is arranged in curls, and these are very clearly rendered around the face and brow. The head has beetling eyebrows and large eyes, these being very skilfully worked. The nose is full and the lips thin. There is a dimple on the chin. The base is flat. This rhiton displays the characteristics of the Roman period and may be dated to the 2nd century A.D.

Seljuk Museum

Perforated Amphora

This is a pot of brick coloured clay with ornamental rim, vertical handles, wide neck, a wide body tapering towards the bottom, and a concave base. There is a hole for a rope to be passed through on each of the vertical handles at a point close to the body. The whole of the amphora is covered with holes. On the shoulder there is an inscription in Greek letters. This is a proper name and must belong either to the maker or the owner of the amphora.

Perforated amphorae were used to keep crabs and lobsters alive in water. This type of pot is used for crabs at the present day by fishers at Kas and Kalkan. Crabs are used as bait for labrets and are kept alive in these pots, which are suspended in sea water, until the fishers are ready to go out lobster-fishing.

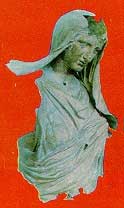

Izmir Museum

This bronze statue, popularly known as the lady from the sea is the most important underwater find in the Izmir Museum. The statue represents a mature woman in a melancholy attitude. The head is bent slightly forward and the hair visible beneath the head covering is combed backwards from each side of the forehead. The top, the back and the section below the waist are broken and missing. She is wearing a himation which covers her head and left breast and is then wound round the body in folds, to pass under the right breast. Under the himation she is wearing a peplos which folds in such a way as to reveal the right breast. At the neck a part of the chiton can be seen beneath the peplos.

Perforated amphora

According to Ridgeway this is a standing female statue. This is indicated by the treatment of the breasts and the absence of folds at the waist. Ridgeway, however, does not agree that the melancholy attitude and the veil necessarily indicate that this is a statue of Demeter. Veils were also worn by mortals and by several other goddesses. It is thus doubtful whether the statue represents a mortal or a goddess. It remains, however, one of the most important finds of classical archaeology.

The statue may be dated to the beginning of the 3rd century B.C.

Istanbul Archaeological Museum

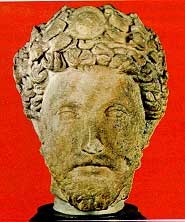

Head of Marcus Aurelius

This head has short curly hair and an abstracted expression. On the hair is a wreath of leaves with a cameo in the middle. The tip of the nose and beard are broken. The back and top of the head are summarily treated. The head, which is larger than life-size, is broken off at the neck. It is made of large grained white marble and on it, particularly in the hair, can be seen sediment left by colonies of sea animals.

This head of Marcus Aurelies (161-180 A.D.) was found in the sea off Ayvalik and sent to the museum by a person of the name of Baltaci Bey in 1889.

Kantharos

This is a black burnished pot. Missing are the handles and a section of the rim. It is decorated with a ring of engraved palmettoes and dots. The surface is covered with sea anemone’s and sediment.

This drinking goblet may be dated to the end of the 4th century B.C. or to the Hellenistic period.

Fethiye Museum

Although this is a small museum it contains a large number of underwater finds. These include amphorae and 34 green-glazed Byzantine plates with stylised animal and vegetal motifs.

The most interesting exhibit in the museum is the statue of a saint made from red pine. This statue had been used as a figure head in a Christian ship.

Statue of a Saint

The statue stands on a pedestal. The hair is parted in the middle and hangs down over the shoulders in two plaits. The ears are carefully rendered. The head and body are thrown backwards. The left arm is held close to the body and holds an anchor in the hand. The right arm, which crossed over the breast, is broken and missing. The right hand may have held a ship’s rudder. The figure is wearing a jacket there is a long skirt with tassels flying slightly to the read. Gilt paint was used in the statue. The hair and eyebrows were blue, the lips red and the skin white. The large nails at the back of the statue show the figure was fastened to the ship’s post.

The type of costume indicates a date towards the end of the 19th century.

Antalya Museum

Antalya is one of the oldest museums in Turkey and contains a large number of underwater finds, including a collection of 130 plates, various amphorae, braziers, lamps and earthenware pots.

Plate

This is a well-preserved plate of brick coloured clay, cream glazed inside and unglazed outside, with a short broad body and raised base. The decorations and figures on the plate are engraved, and include a stylised animal figure resembling a stag moving towards the right and contained in a number of circles. The head of the animal is turned back, and the empty spaces above and below are filled with other stylised animals. Below there is an animal with long ears, while above there is a squatting animal facing in the opposite direction. These three figures are contained within a circle in such a way as to leave no empty spaces between them. This find was recovered from a wreck off Kas.

This plate can be dated to the late Byzantine period and shows traces to Persian influence.

This is made of an unshipped light brown paste with a round rim, a cylindrical body tapering towards the bottom and a base. On the shoulder there is a wide handle and a vertical spout. Between the spout and the neck there is a small ring handle which allowed the pitcher to be hung up without any of the contents spilling. There is a deep crack in the body. The surface of the pitcher is covered with the remains of sea anemone’s and colonies of sea animals. This type of pitcher was specially made for use on board ship.

This pot is made of brown paste with an oval body tapering slightly towards the base, a sharp rim, a slightly rounded base and high vertical handle. Right opposite the handle is a large open spout. The pot belongs to the Hellenistic period.

This is of red paste with black slip, and has a projecting rim, a long nock, a slightly concave handle, and a wide body, with a conical handle at the base. This had been used as a perfume bottle. This is a small example of the Knidos type amphorae of the 3rd century B.C.

Pot

This is made of basalt, which is a rather difficult stone to work but which is resistant to heat. It has a cylindrical body tapering slightly towards the top, and a flat base. On the body are horizontal handles. This type of pot is known to have been used in the Roman period.

Side Museum

Bronze Artemis

With her right hand she is taking an arrow from her quiver, while with her left hand she is holding the bow. Her hair is gathered up on the top of her head. She is wearing a double layer of clothing, through which the form of the breasts are reflected. The weight of the body rests on the right foot.

This bronze figurine of Artemis may be dated to the Roman period.

Head of Apollo

This is of white marble. The head is turned to the left from the neck. The hair is parted in the middle of the forehead and is combed towards the back in wavy locks. At the back of the hair is a band in the form of a plait encircling the head. The plait in the form of a horn on the top of the head is broken and missing. The figure has a triangular forehead, a broad nose and slightly open mouth. The back of the head is broken and missing. There is sediment in the curl of the hair and behind the ears. This may be dated to the middle of the 2nd century.

Alanya Museum

Sea Monster

This is of pink marble, and consists of a body in the from of a head and a foot. The head is that of a lion, with pointed ears, open mouth and protruding tongue. The eyes, nose and mouth are skilfully rendered. A moustache is visible under the nose, while in the centre of the forehead there is a deep groove. The lion’s mane is well rendered. The body is in the form of an ‘S’. On the body can be seen round projections and acanthus leaves. The body ends in lion’s paw. The claws are out, and the muscles of the legs are rendered, as well as the knee joint and the bone projection behind. There are clamp sockets in the neck and under the leg. This object was probably used as a ship’s figurehead.

Carthaginian Amphora

This amphora is of brick coloured clay, with a thick ornamented rim, a handle in the form of a band, a cylindrical body without neck tapering slightly towards the bottom, and a cut base.

This may be dated to before 146 B.C. when Carthage was destroyed by Rome.

Silifke Museum

Diver’s Ring

This ring is made of limestone. The side to which the rope is to be attached has a square projection with a hole in the middle for the rope to pass through. There is one of these stone rings in both the Antalya and Bodrum Museums. It has proved impossible to date them.

Right up to recent times divers have carried heavy stones which pull them down to the bottom of the sea. They then let go of the stones and come up to the surface with the sponges they have gathered.

Source : Underwater Archaelogy In Turkey 1975

By : Oguz Alpözen